“The Ghetto” (1919), by Lola Ridge, an early 20th century radical anarchist poet, is a twenty-page, Modernist poem depicting the daily life and struggles of immigrant Jews, especially women, at the turn of the 20th century in New York City. Around 2 million Eastern European Jews arrived in New York City between 1881 and 1922 through Ellis Island, many of whom found work in sweatshops in the garment industry. Overall, “The Ghetto,” celebrates the lives and political struggles of these immigrants living in poverty. Although Ridge was not a Jewish immigrant herself, she rented a room in an apartment on Hester Street living with a Jewish family and thus became acquainted with this community. “The Ghetto” concerns itself with the intersection of early 20th century exploitative labor practices, the developing liberatory politics of the labor movement, poverty, race and religion. The speaker of “The Ghetto,” is one who can never fully position herself within the “cramped ova,” of the ghetto. As Nancy Berke asserts, she acts much, “like a director opening a film.” When Ridge attempts to penetrate this community, she is often rebuffed by the very characters she creates. This talk investigates whether Ridge’s psychologically distant depiction of this community has anything to do with her own subject position as a woman, politically engaged anarchist, Anglo-immigrant and non-Jew. What does it mean to write about and aestheticize a community that is culturally alien from one’s own and how have the politics around these writing practices changed in the last century? This paper looks to revisit Ridge’s poem by examining the ethics of writing about communities of otherness, and seeks to find which practices verge on objectification and if so, how? By comparing Ridge’s depiction of Jewish life to Jewish to a Jewish poet, Morris Rosenfeld, who wrote about the immigrant experience and labor around this time, I would like to think about these differences and investigate issues of cultural representation, identification and appropriation.

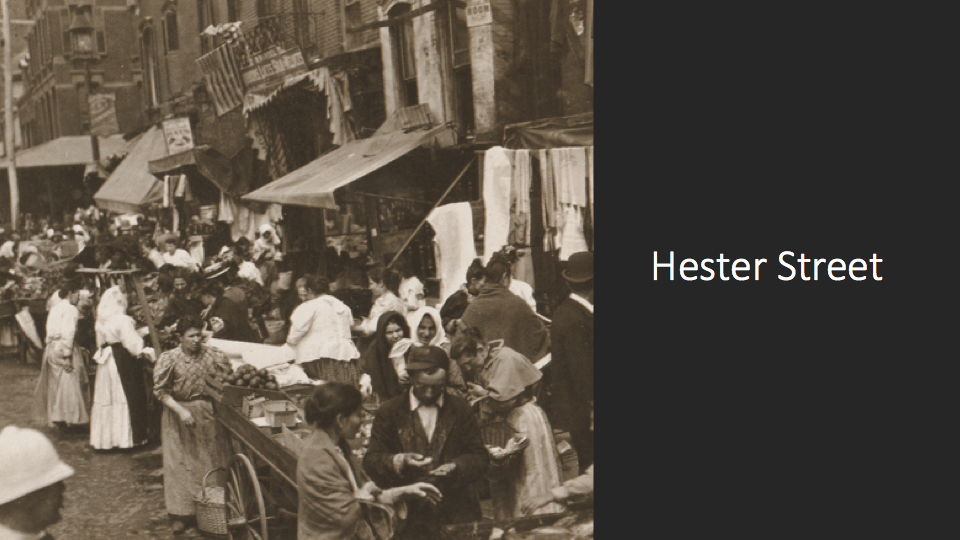

The first thing that I want to do is to take a look at the superficial stereotypes that are employed and will be immediately recognizable in “The Ghetto.” The first stereotype, one that is used transhistorically when it comes to immigrants in the United States—that that their bodies are not defined as singular. Instead, they are seen as one mass of people. It is important to note that when “The Ghetto” was written in 1919, the racial categorization of Jews was in flux and confused. Early 20th century immigrants were organized and oppressed by elaborate ethnic hierarchies in their slow process of assimilation into the dominate culture. The Jews who settled around Hester Street in Manhattan were largely Eastern European Jews of Ashkenazi decent and would have looked fairly white in terms of skin tone, but they were not necessarily seen by others as such. “The Ghetto,” begins with a panoramic look at Hester Street where Jewish bodies “dangle from fire escapes,” the faces of the immigrants are “herring-yellow / spotted as with mold.” The word “yellow” here feels important when looking at race.

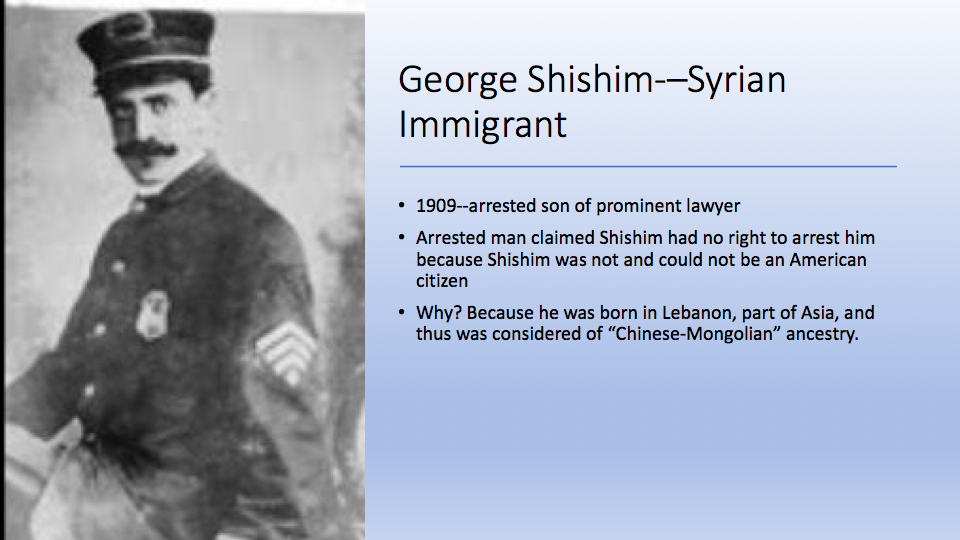

And here I’m going to provide a little bit of history to give you an idea about the slippery categories of race and ethnicity at this time in order for dominant groups in America to stay in power: “In 1909 George Shishim (an immigrant from Syria) acting in his capacity as a policeman in Venice, California arrested the son of a prominent lawyer for disturbing the peace. This incident started the legal fight for Shishim’s eligibility to citizenship. The arrested man claimed Shishim had no right to arrest him because Shishim was not and could not become an American citizen, because he was not of the “white” race. Having been born in Lebanon, part of Asia, Shishim was considered of Chinese-Mongolian ancestry.” When a Los Angeles court determined he was a white man, the LA Times reported it made every feature of his dark, swarthy countenance radiate with pleasure and hope.”

To continue how immigrants are depicted in “The Ghetto,” Ridge likens Hester Street to a river “with its hot tide of flesh / that ever thickens.” The bodies move in “heavy surges,” that are “clavering like surf.” She also describes the bodies as, “litter from the East.” The word “litter,” here is interesting for its double meaning. From the outset of the poem, it’s the mass of people that is important and distinct. As the poem moves to the apartment where Ridge has rented a room, she focuses in on more detailed descriptions of her characters including Sodos and his daughter Sadie, with whom she lives. Sadie works in a factory by day and goes to protest meeting at night, something that Ridge admires (recall that Ridge herself is an anarchist and activist) as she describes Sadie as a “fiery atom.” Sadie’s hair is “wet-black,” and her face is “too white.” Interestingly, it’s not that Sadie’s skin is white, but rather that the dust from the machines that she works on as well as her fatigue that makes her white which is an interesting link between capitalist labor and whiteness. In the next section of the poem, Ridge describes two more young women who work in the garment industry. One of them named Sarah, Ridge describes as “swarthy,” with an “olive throat.” One can’t help but link the word “swarthy,” here with the derogatory way in which “swarthy,” is used to describe Shishim’s skin in the LA Times.

Children in “The Ghetto,” are most noticeably written about as an undifferentiated mass. Most of them are “sturdy,” except one girl, who Ridge says “stands apart.” The little girl has braids that are “shiny as a blackbird’s,” and her eyes have the “glow of darkened lights.” When Ridge offers the little girl an orange, which would seem to be a universal gesture of goodwill, the little girl doesn’t seem to understand. Then, when Ridge takes the girl’s hand and puts the orange in it, she describes the girl’s hand as “as stiff as a doll’s,” and that the child runs off in a “white panic.” This interaction between the speaker and the little girl sheds some light on how Ridge both feels and is seen as an outsider within this community. The little girl speaks no English, only speaks Yiddish, and Ridge confesses that she doesn’t understand what the child is saying. These are the kinds of textual clues that tell us that perhaps Ridge is not particularly welcome in these Jewish cultural spaces. In her paper, “Ethnicity, Class and Gender in Lola Ridge’s “The Ghetto,” Helen Berke, sees Ridge as a “keen and admiring observer,” who takes snapshots of Jewish life with her poem, but what I would add to that “The Ghetto,” also document’s Ridge’s outsider status. If we take a close look at the Jewish characters Ridge creates in the poem, it doesn’t appear that Ridge has any substantial interaction with them, instead choosing to paint pictures of this community from the outside. Why doesn’t she have an emotional attachment to the people she writes about? As a poet with radical leftist politics, perhaps she felt that she needed to depict her subjects with objectivity and remove. Perhaps she was using the Jewish immigrants to make larger political points about human dignity and labor and she felt like the individuals didn’t matter as much as the greater political message. After all, the poem, ends with a kind of abstract affirmation to life: “LIFE! / Startling, vigorous life, / That squirms under my touch, / And baffles me when I try to examine it, / Or hurls me back without apology. /Leaving my ego ruffled and preening itself.” Even in this affirmation, she acknowledges the difficulty in rendering city life which “squirms” under her touch.

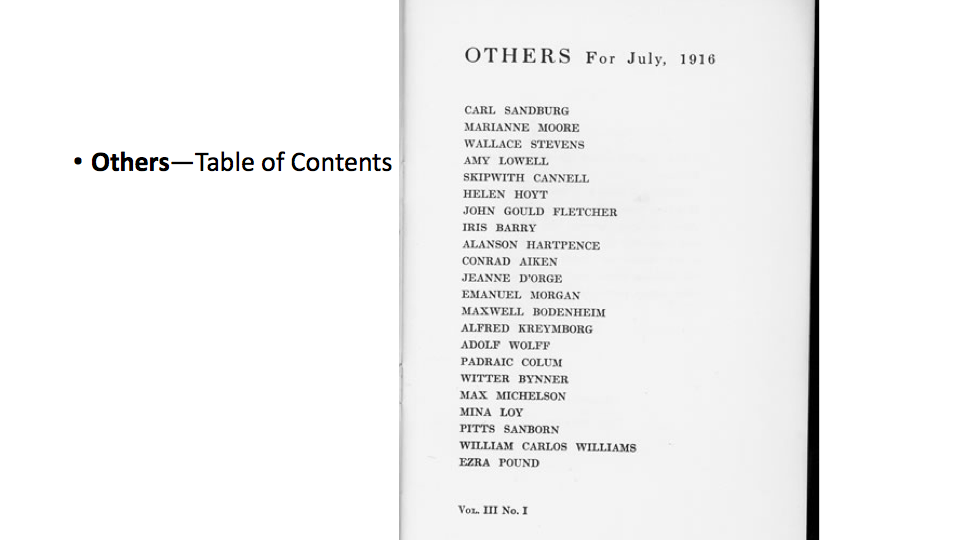

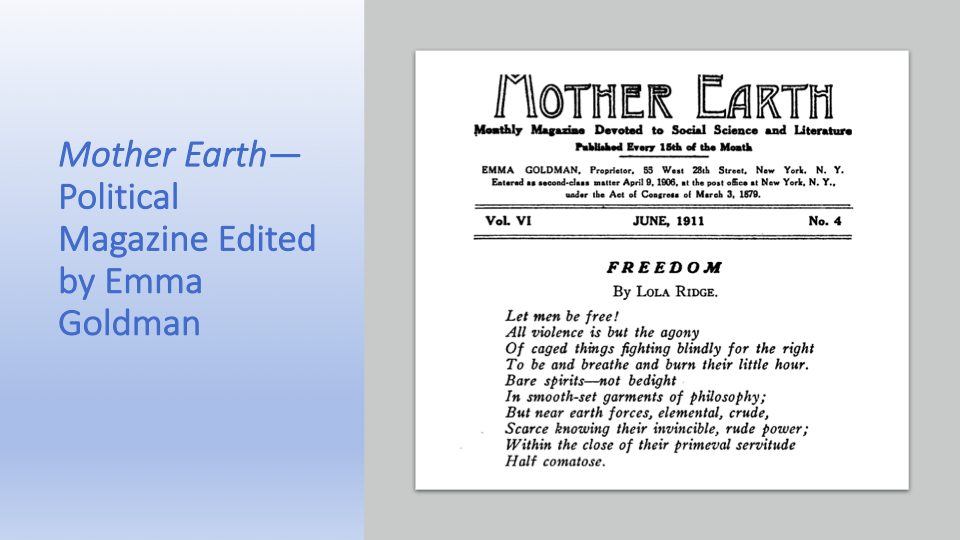

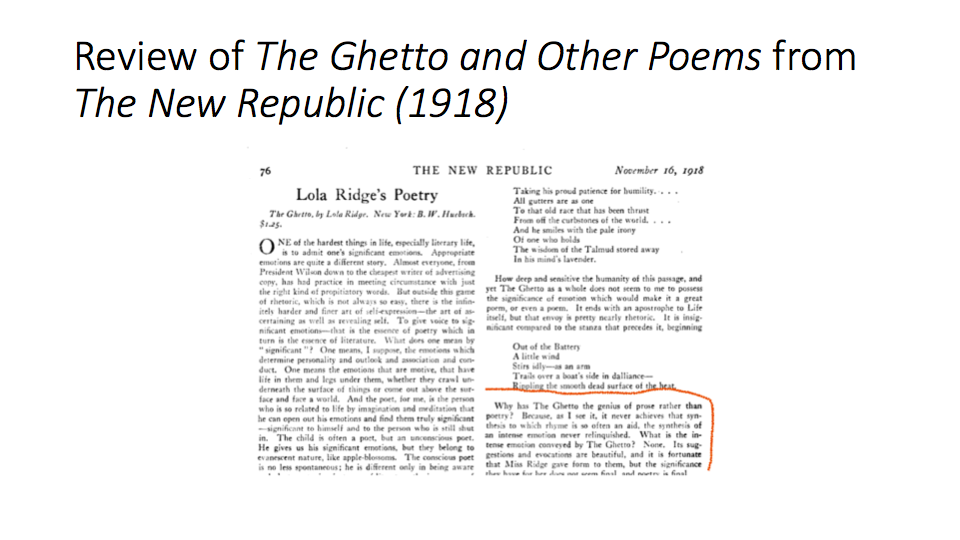

What becomes important, though, is that Ridge, unlike many of her contemporaries writing about the immigrant experience, used Modernist poetic techniques (disjunction, collage, lack of a cohesive rhyme scheme) and published in avant-garde literary journals like Others, Broom and Poetry. Ridge’s sophisticated aesthetic sensibilities allowed her entrance into literary spaces that she would otherwise not have been able to access. Her poems were deeply political and certainly more leftist and overtly political than the other poems published in Broom, for example. But Ridge, much like Claude McKay, also published her poems in explicitly political Socialist and Communist magazines including her friend Emma Goldman’s Mother Earth. In a review of “The Ghetto and Other Poems,” in the New Republic, where Ridge had published work, Ridge is criticized for her poetry not being lyric enough, “hovering between poetry and prose.” In this review, which appears to be one of the only contemporaneous reviews of Ridge’s work, the question of representation and appropriation is taken up. The writer claims that Ridge’s “The Ghetto,” is “beyond a doubt the most vivid and sensitive and lovely embodiment that exists in American literature of the many-sided transplantation of Jewish city dwellers which vulgarity dismisses with a laugh or a jeer. The fact that Miss. Ridge is not a Jewess, is herself alien and transplanted, does not disqualify her work. On the contrary, she is disengaged so that she can move from reality to reality with a purse sense of the food that immerses her.” Even in this review, Ridge’s disengagement is seen as a way to bolster her credibility in authentically depicting her subject.

II.

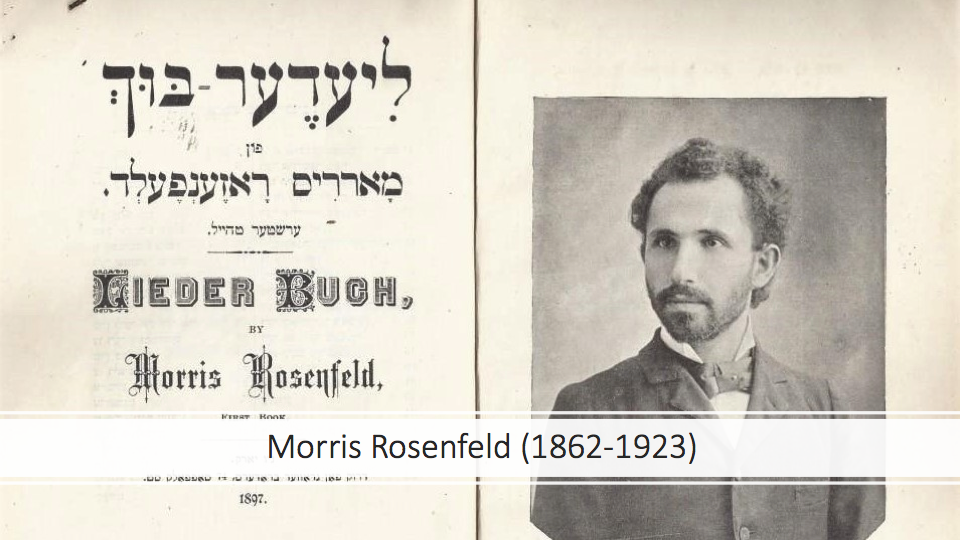

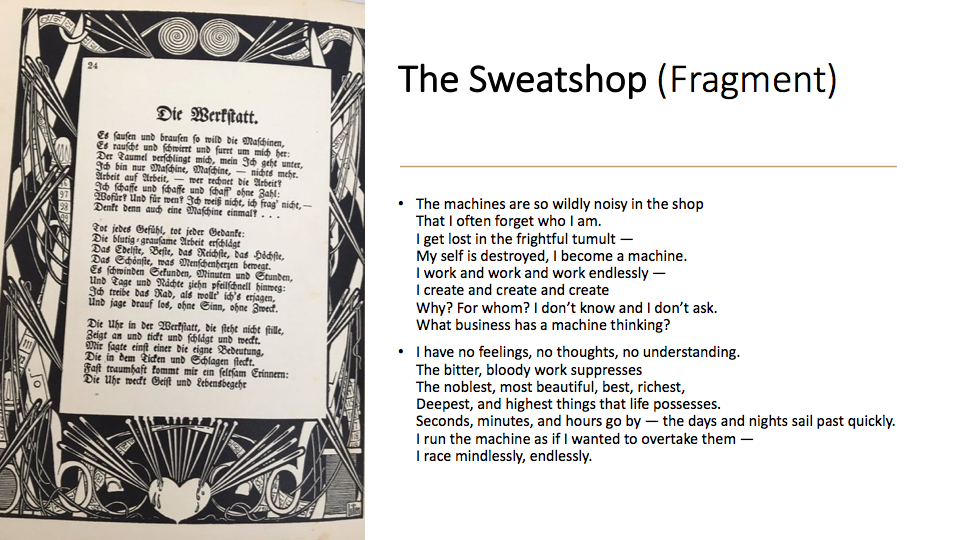

This might be a good time to turn our attention to the poet Morris Rosenfeld. Born in 1862 in Poland, Rosenfeld immigrated to New York in 1886 and worked in sweatshops. He wrote in Yiddish, which was the language used in the home and on the streets for many Jewish immigrants of Ashkenazi descent. The choice to write in Yiddish was an important one because it was a way to stay connected to the old world. In fact, this poem was a source text for Franz Kafka’s Amerika, which shows that there were strong literary connections between the old and new world. But because Morris wrote in Yiddish, his poetry was not able to readily cross into the more fashionable world of modernist poetics though he became very popular as a kind of “poet of the people,” and when he died in 1923, over 10,000 people attended his funeral. The following is an expert of a poem that details his experiences in the factory:

The Sweatshop (excerpt)

The machines are so wildly noisy

in the shop that I often forget who I am.

I get lost in the frightful tumult —

My self is destroyed, I become a machine.

I work and work and work endlessly —

I create and create and create

Why? For whom? I don’t know and I don’t ask.

What business has a machine thinking?

I have no feelings, no thoughts, no understanding.

The bitter, bloody work suppresses

The noblest, most beautiful, best, richest,

Deepest, and highest things that life possesses.

Seconds, minutes, and hours go by —

the days and nights sail past quickly.

I run the machine as if I wanted to overtake them —

I race mindlessly, endlessly.

The clock in the shop never rests —

It shows everything, strikes constantly, wakes us constantly.

Someone once explained it to me:

“In its showing and waking lies understanding.”

But I seem to remember something, as if from a dream:

The clock awakens life and understanding in me,

And something else — I forget what.

Don’t ask! I don’t know, I don’t know! I’m a machine!

Now compare Rosenfeld’s poem to Lola Ridge’s character Sadie, a character she creates in “The Ghetto” as representative of the sweatshop worker:

Sadie dresses in black.

She has black-wet hair full of cold lights

And a fine-drawn face, too white.

All day the power machines

Drone in her ears…

All day the fine dust flies

Till throats are parched and itch

And the heat – like a kept corpse –

Fouls to the last corner.

Then – when needles move more slowly on the cloth

And sweaty fingers slacken

And hair falls in damp wisps over the eyes –

Sped by some power within,

Sadie quivers like a rod…

A thin black piston flying,

One

with her machine.

Both poets confront the dehumanizing effects of manual, low-wage labor and in both poems the human becomes “one” with the machine. In Morris’s poem, there is a first-hand account of the self which is fractured and destroyed through this unpleasant process. He says that this “bitter, bloody work suppresses The noblest, most beautiful, best, richest, Deepest, and highest things that life possesses.” There’s simply no time to think for “What business does a machine have thinking?” and “I have no feelings, no thoughts no understanding.” The irony of course is that the poem itself does have a very clear understanding of what happens to a person when working tirelessly in a sweatshop—he can’t seem to hold a train of thought. The clock, fundamental in the dehumanization process, “strikes constantly,” but also “awakens life and understanding in me” (another irony) /And something else — I forget what. / Don’t ask! I don’t know, I don’t know! I’m a machine!”

Sadie, in Ridge’s poem is also at one with her machine. Ridge says that she is, “Sped by some power within, /Sadie quivers like a rod…/ A thin black piston flying, / One with her machine.” Ridge is basically saying the same thing about the machine and the human becoming one, but Sadie is turned into a heroine, rather than a martyr. Sadie, unlike Rosenfeld, goes home to read at night: “her lit eyes kindling the mob.”

Nights,

she reads

Those books that have most unset thought,

New-poured and malleable,

To which her thought

Leaps fusing at white heat,

Or spits her fire out in some dim manger of a hall,

Or at a protest meeting on the Square,

Her lit eyes kindling the mob…

Or dances madly at a festival.

Each dawn finds her a little whiter,

Though up and keyed to the long day,

Alert, yet weary… like a bird

That all night long has beat about a light.

Both of these poems gave me a lot to think about in terms of authenticity, how immigrants have been utilized in art to make political claims and how these depictions may vary depending on who is doing the writing. Certainly, the paradigm about who can write about what has totally changed over the last century. If a poem is aesthetically “good,” or “avant-garde” (which is true in Ridge’s case), are questions of authenticity overlooked? In other words, if her portrayal had been less poetically interesting, would she have even been able to publish her work in these fashionable magazines? Rosenfeld seemed to have a much harder time publishing his work and was seen more as a proletarian poet. Is this because he was writing in Yiddish, or is there something else going on? After all, at some point, he was translated into English by a Harvard professor, but most people that I talk to have not heard of him. But also, Ridge, who has seen a revival in recent years, brings to light not only the plight of Jewish immigrant workers, but specifically the struggles of immigrant women, whom she sees as fierce, political and hardworking, which adds to the feminist canon of radical poems dealing with labor, certainly something that should be celebrated.

*This is a work in progress–will add the Works Cited page and notes later. Thanks to Ben Friedlander for pointing me to Rosenfeld’s work.